"Hallo! A great deal of steam!The pudding was out of the copper. A smell like a washing-day! That was the cloth. A smell like an eating-house, and a pastry cook's next to each other, with a laundress's next door to that! That was the pudding." Charles Dickens, Stave Three, A Christmas Carol, 1843

Fat is the miracle worker of the dessert world. All fats contribute richness, flavor, and melting quality in the mouth; some have special properties for making products more or less flaky, firm, tender, delicate, or earthy. One can debate the relative merits of butter for cakes, lard for pies (and one does). But for steamed puddings, especially of the holiday variety, there can be little argument as to the fat of choice: beef suet.

The suet used in dessert cooking is the protective fat around the kidneys of beef cattle. It has a relatively high melting point, which means that it doesn't melt until the product is structurally sound; this results in a moist, airy grain in a cake or steamed pudding (which is really an unleavened cake) and crisp pastry. Suet is a primarily saturated fat, but it's the holiday season of forgiveness, when we try to overlook faults. Moreover, the rich but clean taste it creates cannot be duplicated with shortening or even butter; in a pudding, such substitution would make it taste greasy.

Like many things in today's era of agriculture on a massive scale, it is increasingly difficult to find good or even real suet. If you live near a farmer who raises beef, let him or her know that you would like some--although you should probably put this request in well in advance. If no farmer is hard by, your next best chance of getting suitable fresh suet is a butcher shop--but of course those scarcely exist anymore. You can buy suet in many markets at this time of year--indeed, you may have to--but you will have to buy more than you need to get a usable amount, because what's available is likely not all true suet and

what is may have been frozen for long periods as well, resulting in a loss of quality. Fortunately, suet is relatively cheap and buying a lot in order to sort through it is possible. For the recipe below, buy at least a pound. Look for suet that appears to be smooth, creamy white to slightly pinkish and somewhat glossy, and in clumps rather than chunks or strands. Choose a package that contains as little fat with a powdery or sawdusty look as possible; this is either old/over-frozen, or not true suet. At home, you will need to pick it over. First, brush or wipe off any loose powder, and begin to pull it apart; it is held together by fine, papery connective tissue that comes right off, leaving you with clean, creamy bits. These are the pieces you want to use. The rest is for the birds, literally. You can thread it on a skewer, securing the end with a small apple to prevent it sliding off, and hang it outside. Recently, a suet product cut in small pellets or shreds has become available, but I have not tried it.

Steamed puddings made with suet include the famous "Spotted Dick," Sterling pudding (a molasses pudding), and a lovely carrot pudding that makes a nice winter dessert. Not only are steamed puddings easy and quite fun to prepare, they make successful, welcome gifts: many people have never tasted one, and are pleasantly surprised by their rich, moist, fragrant crumb and undeniably festive serving ritual. You can make small ones in mini bread pans, small coffee bowls, or even muffin tins (use paper liners). A little goes a long way.

The classic, of course, is Plum Pudding, sometimes called Christmas Pudding or Suet Pudding--all slight variations on a theme. I am a little late this year, but generally try to make my plum puddings the Sunday after Thanksgiving to let them ripen for Christmas. In England it is customary to have every family member stir the pudding once as it sits, and this is sometimes called "Stirring Sunday." Plum puddings do not absolutely need to age--they will be very good if you don't get around to making them until a week or even day before--but on the other hand, some aging is beneficial, and even a lot doesn't hurt. I have occasionally found a small, neglected pudding in the back of a cabinet or the freezer from the year before, nearly indistinguishable from the carefully tended. If you want to keep an extra on purpose for Easter or just because, remember to unwrap and douse with brandy from time to time.

Universal Plum Pudding

Though Mrs. Cratchit did confess that she had her doubts about the quantity of flour after her ever-supportive husband declared her pudding "a wonderful pudding"--"not at all a small pudding for a large family"--the fact is that plum pudding is fool-proof: the recipe is completely flexible, the cooking relatively insensitive. So I have written this recipe for plum pudding, which I have been making according to this basic formula for more than 30 years, in a manner that reflects that easy-going quality. Don't for one minute hesitate to try it.

In my family, we eat plum pudding with dinner, served alongside what was the turkey when we were young, and the prime standing rib roast as we became more prosperous. This was yet another of my grandmother's ways: plum pudding is usually served as dessert (we had pies). The sauce is also "her" sauce, at least as close I have ever been able to come to replicating it. Which is pretty close.

Start these a day ahead of steaming (two days won't hurt if things get hectic). Makes enough for molds totaling about 8 cups capacity (although you won't fill them all the way), and to serve a small portion (which is what you want) to 12-14. The recipe may be doubled.

1 3/4 cups beef suet, chopped or ground fine

2 1/4 cups fine fresh white bread crumbs

1 1/2 cups seeded muscats or, if unavailable, another large chewy raisin such as Monukkas

1 1/4 cups other dried fruit, mixed in any proportion or alone (such as currants, cranberries--preferably unsweetened--, apricots, figs, and/or pineapple)

1 cup mixed

citron, orange peel, and crystallized ginger, in any proportion (my preference is for about half ginger)

1/2 cup a-p flour

1 large apple or pear, peeled and chopped (optional)

1 1/2 T Vietnamese cinnamon

1/2 tea ground cloves

1/4 tea cardamom

1/2 tea freshly grated nutmeg

1/2 tea salt

1/2 cup unsulphured molasses (dark or "full flavor," not black strap)

2 large eggs

3/4 cup good but not great brandy, whiskey, or bourbon

Another 1/2 cup or more brandy for soaking and igniting.

For the crumbs: trim crusts of bread, tear into large pieces, and process 'til fine. Use a fine-grained, plain white loaf, not a sourdough or chewy-textured bread.

For the suet: After cleaning and picking over as described above, put in the food processor with a large pinch of flour and process until it looks like your bread crumbs. Don't overdo or it will begin to form a paste; you want it to distribute well into the batter.

To prepare molds: Butter the insides well, paying special attention to crevices. Using the mold as a tracing guide (turn the mold upside-down), cut out a piece of clean white cloth (I use old sheets) to fit the opening. Butter and flour the cloth on one side.

Put all the dry ingredients into a large bowl and toss well. Pour the molasses into a 2-cup glass measure to the 1/2 cup line; add the brandy to the 1 cup line, then beat in the eggs. Pour over the dry ingredients and stir in well. Cover with plastic wrap and let sit on the counter overnight (two is fine). Stir from time to time, adding a little more brandy or some apple cider to maintain a thick but still somewhat fluid texture if it becomes too stiff; do this once more before cooking.

Fill the prepared molds about 2/3 full; with your fingers, press it lightly into any corners, and try to have batter, not fruit, touching the sides. Lay the buttered and floured cloth upside down on the batter, smoothing it down gently. Cover the mold with its lid (if you have pudding molds) or, if using bowls or pans, with aluminum foil secured with kitchen string or double elastic bands (I use elastics, which can break part-way through cooking, but not so soon or often as to matter).

Boil a large kettle of water. You may steam your pudding on top of the stove on a rack in a Dutch oven or other large, deep pan with a lid, or in the oven; this is useful when you are making a lot of small puddings, which you can place on a rack in a big roasting pan and cover with its lid or heavy duty foil. Pour the boiling water around the molds until it reaches half-way up their sides. If using the oven, find the temperature that will keep the water at a simmer--350-400 F. Steam about two-three hours for small-medium puddings and six hours for medium-large; the pudding surface should swell a little, feel firm to the touch, and will pull just slightly from the sides, like a cake; the suet particles will have disappeared. Remove to a rack, remove and discard foil, and gently peel back the cloth and discard. Cut cheesecloth large enough to wrap the puddings and place on the

counter; put about a half-cup of brandy

into a shallow dish. Turn the puddings out smartly onto

the cheesecloth while

they are still hot; they should be very dark, almost black, a sign of good quality, with no visible traces of the suet, all of which should have melted. If any pudding bits remain in the mold, simply lift them carefully and press them down onto the pudding where they belong, smoothing the edges; they will blend right in. Wrap the cheesecloth around the pudding, and immerse into the dish of brandy, turning it over and over until all the cloth is saturated but not drippingly so (press gently to drain excess). Wrap in foil. Once every week or two up to the time of serving, open the foil and douse the pudding lightly; its should be kept moist but not wet.

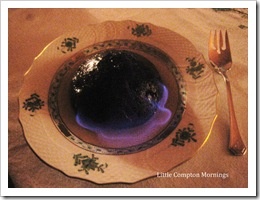

To serve: Place the cheesecloth-wrapped pudding into a steamer and steam for about half an hour (although I confess to having simply microwaved them 'til steaming hot). If you are not the ceremonial type, unwrap, place on a serving plate with a shallow

rim, and serve with the sauce. If you are a traditionalist, top with a sprig of holly, pour a shot-glass of brandy around the pudding, ignite it, and send blazing to the table. Applause is likely (and

de rigueur): take a bow.

Grandma's Pudding Sauce

Grandma's Pudding Sauce

There are many wonderful sauces to accompany steamed puddings. The traditional sauce for plum pudding is hard sauce, which is creamed butter, confectioners' sugar, and flavoring; it goes on "hard" and melts. I don't particularly like it, and neither did my grandmother. Here is the one our family likes--as I have managed to recreate it. I don't think my grandmother used an egg, but I can't get close enough without it; the rest, and the taste, is about right. It's rather boozy (although not nearly as boozy as my grandmother made it); you can cut the liquor in half if you wish--or add more.

1 T unsalted butter

1 T flour

1 cup boiling water

3/4 cup confectioner's sugar (10x), generous, or scant 3/4 cup white sugar

1/4 cup bourbon or whiskey, more or less

1/4 tea or more freshly grated nutmeg

1 large brown egg

In a one-quart saucepan, melt the butter and stir in the flour (i.e., make a roux), being careful not to let it color at all. Let it bubble nicely and then gradually stir in the water

until thick. Add the bourbon or whiskey and let it bubble for a minute or so, stirring. In a small bowl, beat the egg and beat in the sugar and a pinch of salt. Take the pan off the heat and slowly whisk in the egg/sugar mixture; stir in the nutmeg. Put the pan back

on the heat and, over moderately low heat, let it bubble again for another minute or two. The sauce should remain smooth and the egg should not cook. It should look translucent, speckled, and pale beige. Taste, and add more nutmeg or liquor if you like. Remove and pour into a small pitcher or bowl; if all goes well, no need to strain. Refrigerate if you make it the day before; it will keep nicely for several days. Reheat slowly to just barely warm/to restore fluidity.